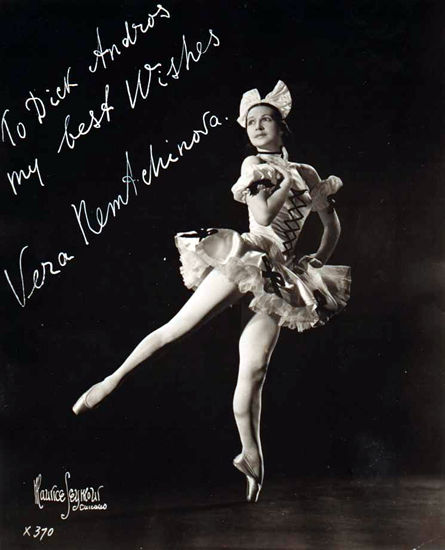

Vera Nemtchinova (1899-1984)

Vera Nemtchinova was born in 1899 in Moscow and began her ballet studies at the age of ten with the private teacher Ekaterina Ivanovna Nedidova. Later she began studies with Elizabeth Anderson. In 1915, after three months with her new teacher, Nemtchinova was seen by Serge Grigoriev, who engaged her as a member of the corps de ballet of Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. Her first solos were the Mazurka and Pas de deux (with Alexandre Gavrilov) in Les Sylphides in 1916.

Madame told me that while she was in the corps de ballet she would learn the roles of the ballerinas by watching from the wings, knowing that one day the star might be unavailable and she would be ready to take her place.

Nemtchinova was called "Little Vera" by Diaghilev, who promoted her to prima ballerina in 1924. She created her most famous role in Bronislava Nijinska's Les Biches in 1924. She also created roles in Les Tentations de la Bergère (1924), Les Matelots (1925), and danced leading roles in Giselle, Swan Lake, Coppélia, La Boutique Fantasque, and Pulcinella. A famous story about Nemtchinova's relationship with Diaghilev relates that when Diaghilev saw her modeling her costume for Les Biches, he commanded Grigoriev to bring him scissors. Diaghilev cut off the collar, making a low-cut neckline, and proceeded to cut off the skirt until Nemtchinova's behind was barely covered. She remarked, "I feel naked." "Then buy a pair of white gloves," he retorted. The gloves became part of the choreography. Nemtchinova told me that Diaghilev didn't want her to wear a headpiece.

In 1927 Nemtchinova and Anton Dolin formed their own company, with Anatole Oboukhoff, and toured Europe until Dolin left the company to return to the Ballets Russes. Before leaving, Dolin choreographed Rhapsody in Blue for Nemtchinova. Diaghilev did not like the music and thought it unsuited for ballet; he disliked jazz. Even when George Gershwin played it for him, Diaghilev said, "Good Jazz -- poor Liszt."

Nemtchinova was also the prima ballerina of the State Opera in Kaunas, Lithuania (1930-35), ballerina with René Blum's Ballet Russe (1936), Col. de Basil's Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo (1939), and guest artist with Ballet Theatre (1943) and The San Francisco Ballet (1946).

Nemtchinova's private life didn't seem to suit the lady that I saw almost every day for eleven years. Nijinsky's friend, Romola, was jealous of her future husband's interest in Nemtchinova. Leonide Massine claimed that he had a romance with Nemtchinova. Nicholas Zverev was her lover and then her husband; but she divorced Zverev and married Anatole Oboukhoff. That partnership lasted until 1962 when Oboukhoff died of pneumonia after a fire forced them out of their apartment, leaving them to stand in the rain on a cold winter night.

Nemtchinova told me many stories of her days with the Ballets Russes. One story made me wonder if she was telling me the truth. Further research confirmed her story. Many of your grandparents or great-grandparents may have told you that they saw Vaslav Nijinsky dance. I don't want the burst your bubble, but that may not be the case. Nicholas Zverev (1897-1965), a Russian dancer who joined Ballets Russes in 1912 (and for the first four years was just one of the dancers) looked like Vaslav Nijinsky and sometimes danced in place of the great star, even though Nijinsky's name appeared on the program. Zverev stayed with the company until 1926 and then toured with his wife Vera Nemtchinova.(who later divorced him and married Anatole Oboukhov). Zverev opened a school in Paris. In the early fifties when I had planned to dance in Europe, Nemtchinova gave me a care package for him. Unfortunately, that was when I injured my foot permanently and a friend of mine had to deliver the package.

Personal Memories of Vera Nemtchinova and Anatole Obouhkoff

Eddy Green was the only person I knew when I arrived in New York City, and it was Eddy who took me to Ballet Arts, Studio "61" in Carnegie Hall. After three years of training and performing with the San Francisco Ballet Company, I was going to take my first class in the Mecca of dance. As sophisticated as I tried to be, I was in awe of what I saw. The great stars of ballet that I had seen on stage were taking the same class that I was. I dressed in the small dressing room, listening to the stars kid each other.

When I entered the studio, I stood next to my friend Eddy, waiting for the teacher to enter. I knew of this teacher because the ad for Ballet Arts in Dance Magazine had used the picture of Madame Vera Nemtchinova for years. In the doorway stood this image silhouetted by the light from the waiting-room behind her. With a halo surrounding her she looked like a vision from another time. As she entered the room I could see her clearly; she was not like any other woman I had ever seen. It was love at first sight. She was wearing a blue leotard and chiffon skirt that she had tucked in front of her leotard. Nemtchinova was in her late forties and sported the most beautiful legs I had ever seen. Her tiny feet were encased in blue ballet slippers trimmed in silver (made specially for her by Capezio). She started to speak with the heaviest Russian accent I had ever heard, and if I had to learn Russian to be in her class, I would have.

I spent eleven years, on and off, studying with Madame. The first day she referred to me as "Gentleman" and until her death I remained "Gentleman." She once told a friend of mine that I was the best student she ever had. "I only have to tell him once." I did everything she said, or died in the attempt to be as perfect as she thought I could be. I had to listen very closely for fear I would miss one of her corrections, and I mentally had to translate every statement instantly. To this day I can relive most of her classes.

Sitting in a chair she would slap her ankle and say, "Vat's this?"

I would reply, "Ankle."

"That's right! Uncle! Uncle! Uncle!" -- slapping her ankle harder with each "Uncle."

To demonstrate the correct head and arm position in arabesque, Madame would hold her arm out so her hand was at nose level and say, "Look at diamond ring," pointing with the other hand to her ring finger.

She would often bend over and lift her gorgeous leg in arabesques and then drop the leg without lifting her upper body and say, "See, you look like washer-woman." Then standing upright in arabesque she would again lower her leg and say as she walked away, "You walk like pr-r-rincess."

After demonstrating a combination, she would have the class stand in fifth position and she would call out (over my head, because by now she knew I had learned the answer), "Vat's first you do?" A new-comer might reply glissade or jeté, but she would gruffly reprimand, "No! No! Plié! Plié!"

"There's no hobbits in ballet -- this today," she would say, striking a beautiful pose, "That tomorrow," adjusting to a grotesque position.

With a pained expression on her face, a girl stepped onto pointe. Madame was quick to correct, "No! No! You must make look easy -- so people see -- go home -- try -- and br-r-roke foot."

And there was the day that a number of her students had told her of their physical ailments. Class started as usual and we had gotten to ronde de jambe exercise when she walked to the door, and turned around in disgust and said, "I can not teach hospital class," and walked out.

Her exaggerated hands were Nemtchinova's trademark. One day a young dancer emulated her hands and Madame gently slapped her hand saying, Madame all right -- you no."

I can't count how many times I heard her say to me, "Gentleman you show."

Sometime you would swear she was in another world that the rest of us could never enter. I remember the day she stood in front of the class to demonstrate the adagio. The music started; with her arms in repose she started her plié and then began a port de bra. Watching her demonstrate was like seeing a textbook come to life, but this adagio went on and on, I know everyone in class was enthralled by what they were seeing and, at the same time, they were trying to remember the first part of the adagio. She dance for at least five minutes and when she was finished, she turned to the class, and received a thunderous ovation from her students and said, "Now we do allegro." The students stood with their mouths wide open. There was no mention that we should try to do her adagio. I for one was personally glad that I didn't have to try to compete with her.

There was a time when ballerinas dressed and acted like the stars they were. Madame always dressed to come to class, and left the same way. By chance, I rode the elevator with her. She had on a pill box hat with a veil, a two-piece suit, high heeled shoes and to top it off, a fur stole. the highest of high fashion was her daily wear. We both left Carnegie Hall and walked toward Sixth Avenue with her telling me what was wrong with my dancing. By the time we were in front of the Russian Tea Room she struck a wide second position plié with a port de bra and said, "Gentleman, you no plié."

Frederic Franklin told me of an event that occurred when Nemtchinova applied for her American Citizenship. She was asked to name three American Generals; after a little thought, she said, "General Electric, General Motors and General Mills." She got her citizenship.

Because of Nemtchinova's technical brilliance doing fouetté turns, Anton Dolin insisted that she insert the third-act fouettés of Swan Lake after the white swan' pas de deux. Nemtchinova always thought this insertion marred the ballet, but her overall artistry compensated for the mutilation of Ivanov's choreography.

Her second husband, Anatole Obouhkoff, would often watch her class and eventually alternated teaching with her. I never studied at the School of American Ballet where he was a major teacher, so this was my chance to study with this great teacher.

Mr. Obouhkoff knew that I was a fanatic about ballet terminology. In class he would call out steps and then ask me to demonstrate. Four out of five times I could. One day Madame was taking class with us and he called on me to demonstrate. I didn't understand him, so I turned to Madame and asked, "What did he say?" She replied, I've lived with him for years and never understood. him."

One of Obouhkoff's most quotable quotes was, "If it is not pretty, then it is not correct." Many of the other students questioned me when I would laugh in class as he shouted angrily at us. I can only say that I was always invited to Russian Easter dinner with these two wonderful people.

At Easter dinners, Obouhkoff tried to teach me to drink vodka. He taught me to dance, but failed in getting me to drink vodka straight -- you can't win them all.

The love I have for this couple will probably be the greatest of my life. When I injured my ankle and was in a cast to the knee and on crutches, Nemtchinova cried. The doctor told me I would have to wear a steel brace just to walk. Obouhkoff encouraged me to discard the brace and get back to dancing. I will always be indebted to them, and I am your teacher today because of them.

(First published December 1995)