The Catastrophist-Cornucopian Debate

The catastrophist maintains that there are natural limits to human exploitation and transformation of the Earth that cannot be transgressed without disaster and that the current scale and rate of human activity already exceed the globe's carrying capacity, defined as the maximum demand it can support without lessening the demand that it will be able to support in the future.

The cornucopian dismisses human carrying capacity as a meaningless concept. It holds that human ingenuity and adaptation through technological and social responses, not natural limits, set the boundaries of human wealth and well-being. It envisions no resource shortage or pollution problem with which society cannot cope.

In interpreting the history of human-environment relations, catastrophists emphasize the rise in human numbers, levels of consumption, and environmental transformation as evidence that pressures on the terrestrial environment are mounting to dangerous levels that threaten humankind's survival. Cornucopians point to rising human numbers, levels of consumption, and life expectancy as evidence of overall and steadily increasing success in the use and management of the Earth. (Meyer and Cuff, 2008).

Current debates between catastrophists and cornucopians are a continuation of debates that have raged for many decades. The following are some pivotal historical figures in the debate over population and resources.

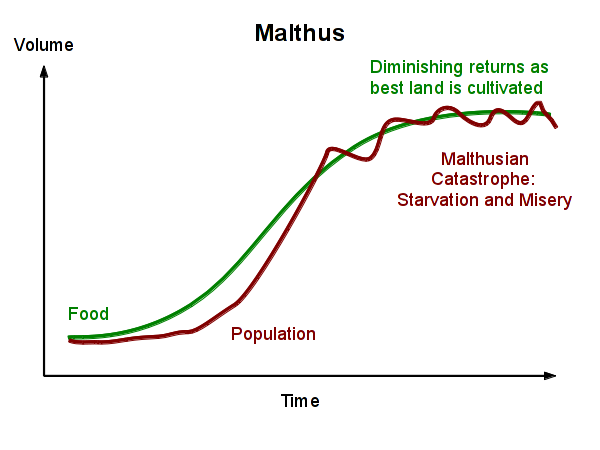

Thomas Malthus

Thomas Malthus (1766 – 1834) was an English cleric and scholar who has been highly influential in the study of political economy. He is the grandfather of catastrophism. He is probably best remembered as asserting in his 1798 book, An Essay on the Principle of Population, that population grows exponentially, while food production is limited by available land. The collision of those two curves results in misery for a large portion of society.

I think I may fairly make two postulata.

First, That food is necessary to the existence of man.

Secondly, That the passion between the sexes is necessary and will remain nearly in its present state.

...Assuming then my postulata as granted, I say, that the power of population is indefinitely greater than the power in the earth to produce subsistence for man.

Population, when unchecked, increases in a geometrical ratio. Subsistence increases only in an arithmetical ratio. A slight acquaintance with numbers will shew the immensity of the first power in comparison of the second.

By that law of our nature which makes food necessary to the life of man, the effects of these two unequal powers must be kept equal.

This implies a strong and constantly operating check on population from the difficulty of subsistence. This difficulty must fall somewhere and must necessarily be severely felt by a large portion of mankind.

Contemporary followers of Malthus' ideas are referred to as neo-Malthusians.

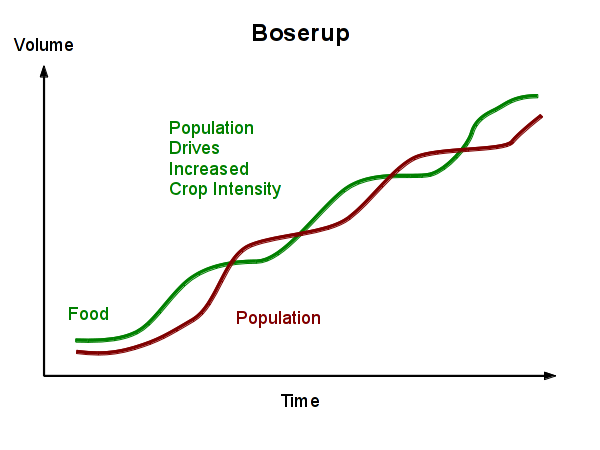

Ester Boserup

Ester Boserup (1910 - 1999) was a cornucopian Danish economist who studied agricultural development. She felt that Malthus had cause and effect backwards. While Malthus believed population growth followed the increased availability of food, Boserup asserted that food production increased in response to increases in population as farmland was cropped more intensively.

She detailed her argument and the evidence for it in her 1965 book, The Conditions of Agricultural Growth:

Ever since economists have taken an interest in the secular trends of human societies, they have had to face the problem of the interrelationship between population growth and food production. There are two fundamentally different ways of approaching this problem. On the one hand, we may want to know how changes in agricultural conditions affect the demographic situation. And, conversely, one may inquire about the effects of population change upon agriculture.

To ask the first of these two questions is to adopt the approach of Malthus and his more or less faithful followers. Their reasoning is based upon the belief that the supply of food for the human race is inherently inelastic, and that this lack of elasticity is the main factor governing the rate of population growth. Thus, population growth is seen as the dependent variable, determined by preceding changes in agricultural productivity which, in their turn, are explained as the result of extraneous factors, such as the fortuitous factor of technical invention and imitation. In other words, for those who view the relationship between agriculture and population in this essentially Malthusian perspective there is at any given time in any given community a warranted rate of population increase with which the actual growth of population tends to conform.

The approach of the present study is the opposite one. It is based throughout upon the assumption--which the author believes to be the more realistic and fruitful one--that the main line of causation is in the opposite direction: population growth is here regarded as the independent variable which in its turn is a major factor determining agricultural developments.

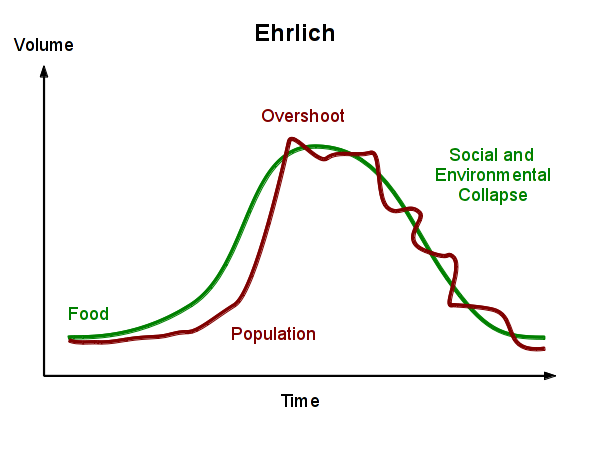

Paul Ehrlich

Paul Ehrlich (b. 1932) is a catastrophist American biologist best known for his warnings in the late 1960s and early 1970s about the consequences of unconstrained population growth.

As public concern over pollution and the ecological health of our planet grew over the 1960s, Ehrlich published a best-selling book in 1968, The Population Bomb, that asserted there were three fundamental issues:

Too Many People ...the world's population will continue to grow as long as the birth rate exceeds the death rate; it's as simple as that. When it stops growing or starts to shrink, it will mean that either the birth rate has gone down or the death rate has gone up, or a combination of the two. Basically, then, there are only two kinds of solutions to the population problem. One is a "birth rate solution," in which we find ways to lower the birth rate. The other is a "deathr ate solution," in which ways to raise the death rate -- war, famine, pestilence -- find us. The problem could have been avoided by population control, in which mankind consciously adjusted the birth rate so that a "death rate solution" did not have to occur.

Too Little Food ...All of this boils down to a few elementary facts. There is not enough food today. How much there will be tomorrow is open to debate. If the optimists are correct, today's level of misery will be perpetuated for perhaps two decades into the future. If the pessimists are correct, massive famines will occur soon, possibly in the early 1970's, certainly by the early 1980's. So far most of the evidence seems to be on the side of the pessimists, and we should plan on the assumption that they are corect. After all, some two billion people aren't being properly fed in 1968!

A Dying Planet ...I have just scratched the surface of the problem of environmental deterioration, but I hope that I have at least convinced you that subtle ecological effects may be much more important than the obvious features of the problem. The causal chain of deterioration is easily followed to its source. Too many cars, too many factories, too much detergent, too much pesticide, multiplying contrails, inadequate sewage treatment plants, too little water, too much carbon dioxide --- all can be traced easily to too many people.

To see Ehrlich and some of his disciples, view this video on The Unrealized Horrors of Population Explosion.

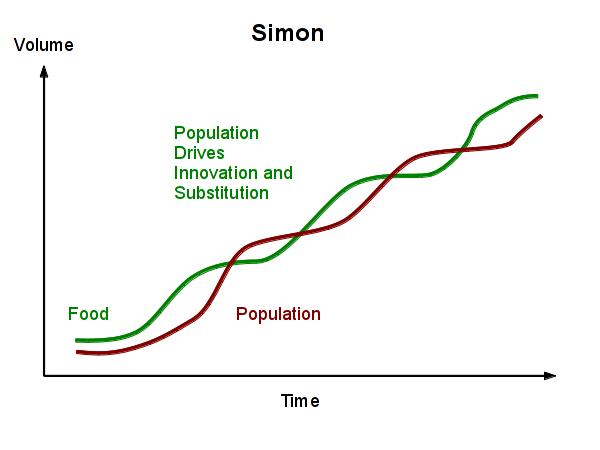

Julian Simon

Julian Simon (1932 – 1998) was a cornucopian American economist. In contrast to Ehrlich, Simon asserted that population increase is actually a good thing because more people means more innovation and production to overcome prior limits.

In his 1981 book, The Ultimate Resource, Simon also asks questions about the values implicit in neo-Malthusian assessments:

Whether population is now too large or too small, or is growing too fast or too slowly, cannot be decided on scientific grounds alone. Such judgments depend on our values, a matter about which science is silent.

...It is sometimes said that some people's lives are so poor and miserable that an economic policy does them a service if it discourages their births.

...There is misery in India...And yet these people must think their lives are worth living, or else they would choose to stop living... Because people continue to live, I believe that they value their lives. And those lives therefore have value in my scheme of things. Hence, I do not believe that the existence of poor people -- either in poor countries or, a fortiori, in the US -- is a sign of "overpopulation."

Ehrlich and Simon became connected in the public mind based on a wager they made in 1980 that the prices of five metals—chromium, copper, nickel, tin, and tungsten—would rise over the next decade. Simon won - all prices dropped, but Ehrlich continued to maintain that the fundamental trajectory of society was still the same, and efforts to postpone the inevitable would only make the inevitable worse.