West Side Urban Renewal

Dense development of the Upper West Side largely occurred in the last two decades of the 19th century. The arrival of the Ninth Avenue elevated rail line in 1879 opened the neighborhood to upwardly mobile middle class families. By the end of the 1920s building boom, Central Park West, West End Avenue and Riverside Drive were lined with fashionable high-rise apartment houses, while the cross streets were dominated by low-rise brownstones.

The economic travails of the 1930s lead to subdivision of many of the rooms in the area as well as poor maintenance for buildings overall. After World War II, African-Americans and Hispanic immigrants replaced middle-class Irish and Jewish residents as the housing stock and quality of life in the community continued to deteriorate (Gratz, 2010, pp 199)

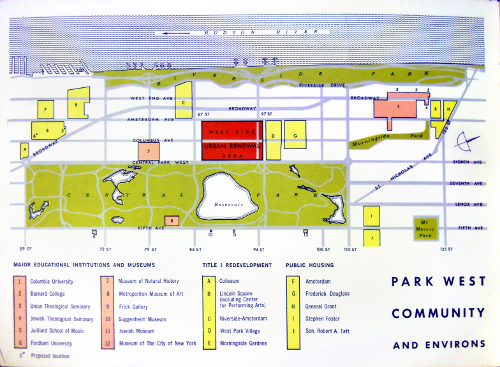

The West Side Urban Renewal began in 1955 when Mayor Robert F. Wagner directed James Felt of the City Planning Commission to study housing deterioration and social unrest on the West Side (NHCPC, 1979, pp 1-3). The commission issued its study in April of 1958 and released a preliminary plan for the West Side Renewal Area in May of 1959. The area covered 20 blocks bounded by 87th Street on the South, 97th Street on the North, Amsterdam Avenue on the West and Central Park West on the East.

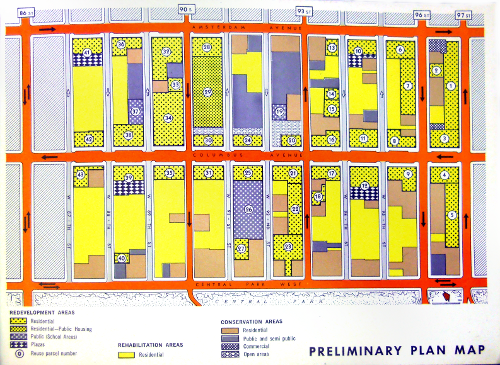

In contrast to the wholesale clearance and rebuild approach of Robert Moses that was used for Lincoln Center to the south and Park West Village to the North, Felt's approach was to selectively demolish targeted structures for private redevelopment (largely along the avenues) while retaining and renovating many of the area's attractive but poorly maintained brownstone structures. The process ended up taking over 15 years longer than planned, with at least two brownstones lingering in dereliction as late as 1995 (Rozhon 1995).

The project can, in some respects, be regarded as a success, with the area becoming one of the city's most desirable (and expensive) by the dawn of the 21st century, although giving the West Side Urban Renewal project sole credit for the revitalization may be a bit of an oversimplification. Wilson (1979) makes a detailed analysis of the transformation by considering the physical, economic, social and institutional environment as well as issues of power and class.

Gratz (2010) argues that the neighborhood was saved by its own virtues (parks, transportation, shopping) IN SPITE of the highly disruptive urban renewal projects foisted upon it. And if Jacobs (1964, pp 187-199) is to be believed, escalating rents as well as homogenious age and architecture may have planted the seeds of the neighborhood's cyclical destruction.

The preliminary plan (linked below) is a fascinating read. Colorful, attractive and full of certitude, it in may ways reads like a contemporary piece of urban planning rhetoric. It's not difficult to imagine the book's outlandish promises coming out of the mouth of Michael Bloomberg, albeit from a firmly privatized rather than public context.

This photo tour roughly follows a loop up Columbus Avenue and back down Amsterdam Avenue

Park Columbus (1986) - 101 West 87th Street

118 West 87th Street

The Centra (1985) - 100 West 89th

600 Columbus Avenue (1989)

600 Columbus Avenue

James Marquis (1986) - 101 West 90th Street

James Marquis

Columbus Avenue west side south of 90th Street

102 West 91st Street (1993)

102 West 91st Street

Wise Towers (1965) - West 90th Street

Wise Towers

Wise Towers

Trinity School (1969) - 100 West 91st Street

Trinity School

Trinity School

Trinity School

100 West 93rd Street (1973)

100 West 93rd Street

100 West 93rd Street

Columbus Ave looking south from 92nd Street

621 Columbus Avenue (1970)

WSURA (Site B - NYCHA) - 74 West 92nd Street (1964)

WSURA (Site B)

Sol Bloom Playground (1972)

Sol Bloom Playground

Sol Bloom Playground

Sol Bloom Playground / 621 Columbus Ave

Brownstone survivors: 61-75 West 92nd Street

PS 84 Lillian Weber School (1972) - 32 West 92nd Stree

PS 84

WSURA (Site B) / PS 84

Columbia Grammar and Preparatory School - 3 West 92nd Street

Brownstones - South side of West 94th Street

Curb extension on West 94th Street

54 West 94th Street looming over West 94th Street brownstones

Brownstones - South side of West 94th Street

Wise Rehab (NYCHA - 1985) - 54 West 94th Street

Looking east down West 94th Street

66 West 94th Street

700 Columbus Avenue (1968)

Columbus Park Towers (1966) - 100 West 94th Street

100 West 94th Street

Art Moderne - 110 West 94th Street (1936)

110 West 94th Street

WSURA (Site A - NYCHA) 120 West 94th Street

WSURA (Site A)

Curb extension on West 94th Street

West side of Columbus Ave south of 94th Street

West Side Marquis (1968) - 70 West 95th Street

Plaza grocery store - 705 Columbus Avenue

70 West 95th Street

70 West 95th Street

70 West 95th Street

70 West 95th Street garage entrance

70 West 95th Street

70 West 95th Street

Brownstones - South side of West 95th Street east of Columbus

70 West 95th Street

70 West 95th Street

70 West 95th Street behind 65 West 95th Street (1928)

Jefferson Towers (1968) - 700 Columbus Avenue

700 Columbus Avenue

95 West 95th Street / 721 Columbus (1969)

95 West 95th Street

Spalling repairs - 95 West 95th Street

95 West 95th Street

95 West 95th Street

The Westmont (1986): 720-730 Columbus Ave

Looking west down 96th Street from Columbus

The Westmont

R.N.A. House (1967): 150-160 West 96th Street (Mitchell-Lama)

150-160 West 96th Street

150-160 West 96th Street

Axton (1971): 733 Amsterdam Avenue / 169 West 95th Street

733 Amsterdam Avenue

733 Amsterdam Avenue

733 Amsterdam Avenue

808 Columbus Avenue

808 Columbus Avenue

808 Columbus Avenue

Sidewalk along west side of Columbus through Columbus Square

775 Columbus Avenue under construction

Union protesting scab labor

775 Columbus Avenue

795 Columbus Avenue

Park West Village - 382 Central Park West

Park West Village - 392 Central Park West

Park West Village

Park West Village - 792 Columbus Avenue

Park West Village - 400 Central Park West

Frederick Douglass Houses

Frederick Douglass Houses

2 Manhattan Avenue

Frederick Douglass Houses

Looking south Down Columbus Avenue from 100th Street

Frederick Douglass Houses

Frederick Douglass Houses

Riverside Health Center (1959) - 160 West 100th Street

Riverside Health Center

Frederick Douglass Houses

Park West Village - 788 Columbus Avenue

Park West Village

Park West Village

Park West Village

PS 163 Alfred E. Smith School: 163 West 97th Street

East River Savings Bank (1926): 743 Amsterdam

733 Amsterdam Avenue

733 Amsterdam Avenue

733 Amsterdam Avenue

701 Amsterdam Avenue (1967)

701 Amsterdam Avenue

701 Amsterdam Avenue

DeHostos Community Center - 698 Amsterdam Avenue

681 Amsterdam Avenue (1929)

681 Amsterdam Avenue: Bas Relief

201 West 93rd

Central Baptist Church (1916) - 166 West 92nd Street

Central Baptist Church

Manhattan Tower, 203 W 90th

Manhattan Tower

Haywood Towers (1974): 621 Amsterdam Avenue

189 West 89th (1997)

189 West 89th

587 Amsterdam Avenue (NYCHA - 1965)

587 Amsterdam Avenue

Glenn Gardens (1975) - 567 Amsterdam Avenue / 171-183 West 87th Street

567 Amsterdam Avenue

567 Amsterdam Avenue

Amsterdam Avenue looking north from 86th Street

Columbus Avenue looking north from 75th Street

William O'Shea JHS 44 (1956)

William O'Shea JHS 44

William O'Shea JHS 44

Parc Belvedere (1986) - 101 W 79th

101 W 79th

386 Columbus Avenue (1988)

386 Columbus Avenue

386 Columbus Avenue

Patagonia, 426 Columbus Ave

West side Columbus Avenue south of W 81st Street

PS 9 - 100 West 84th

PS 9

Gristede's - 500-504 Columbus Avenue (1925)

Louis D Brandeis High School (1965) - 145 West 84th Street

3 Star Coffee Shop - 61 West 86th St

1920's era apartment buildings on South side of 86th Street west of Columbus Avenues